I came acrosss this piece of research and question whether it is too soft on those of us working through our anxiety. Of course, I have spent my lifetime accepting this about myself so I have no further compassion for my enemy! Panic can STICK IT! (unless of course he becomes too ugly ....)

A Compassion Focused Approach to Anxiety Disorders

Abstract: All animals need processing systems that enable them to detect danger and then rapidly take defensive actions to cope and/or avoid them. Anxiety is an evolved mechanism that facilitates such protective and defensive strategies and thus is part of a normal, highly evolved system for threat detection and defence.

Problematic forms of anxiety can occur when evolved mechanisms are triggered inappropriately too intensively, or last too long. The reasons for anxiety becoming "problematic" have been attributed to a complex interaction between genetics, environmental factors, and personal appraisals. This article will explore anxiety difficulties from the compassion-focused theoretical position which argues that the regulation of anxiety occurs both within and outside of the threat system. In particular the system that evolved for attachment processes can be a major regulator of threat processing. Thus anxiety disorders may represent problems in different systems other than the threat system (e.g., soothing system), and attention to those systems is required for recovery This article outlines the rationale and key components of a Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT) approach for the understanding and amelioration of anxiety conditions. A case example highlighting key points is provided.

read more:

International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 3(2), 124–140, 2010

© 2010 International Association for Cognitive Psychotherapy

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Psychology Services, Greater Manchester

West Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust, Bury New Road, Prestwich, Manchester M25 3BL. E-mail:

WELFORD

AN APPROACH TO ANXIETY DISORDERS

A Compassion Focused Approach to Anxiety Disorders

Mary Welford

Greater Manchester West Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust

All animals need processing systems that enable them to detect danger and then rapidly take defensive actions to cope and/or avoid them. Anxiety is an evolved mechanism that facilitates such protective and defensive strategies and thus is part of a normal, highly evolved system for threat detection and defence.

Problematic forms of anxiety can occur when evolved mechanisms are triggered inappropriately, too intensively, or last too long. The reasons for anxiety becoming “problematic” have been attributed to a complex interaction between genetics, environmental factors, and personal appraisals. This article will explore anxiety difficulties from the compassion-focused theoretical position which argues that the regulation of anxiety occurs both within and outside of the threat system. In particular the system that evolved for attachment processes can be a major regulator of threat processing. Thus anxiety disorders may represent problems in different systems other than the threat system (e.g., soothing system), and attention to those systems is required for recovery. This article outlines the rationale and key components of a Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT) approach for the understanding and amelioration of anxiety conditions. A case example highlighting key points is provided.

The DSM-IV (APA, 1994) outlines 12 different anxiety disorders, ranging from simple phobias to obsessive compulsive and generalized anxiety disorders. With collective lifetime prevalence rates of approximately 30% and 12-month rates of approximately 18% (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005) anxiety disorders are one of the most prevalent of all psychiatric conditions in the general population

The CBT view of anxiety disorders, was first described in full in 1985 by Beck, Emery, & Greenberg. They proposed that life experiences and the development of core beliefs and schemas sensitize an individual’s attention and interpretive competencies to certain types of threat, thus triggering evolved and innate threat systems (e.g., fight, flight, freeze, and faint). Experiences of anxiety and fear can sensitize attention systems, create core beliefs (e.g., “I am vulnerable,” “other people are rejecting”) and lead to the development of a range of safety behaviors for coping and avoiding threats.

These safety behaviors typically increase the sense of threat or prevent the learning of adaptive coping or engagement and desensitization (Thwaites & Freeston, 2005).

AN APPROACH TO ANXIETY DISORDERS 125

Over the last three decades however much has changed and advanced in our understanding of the mechanisms that underpin and regulate anxiety (LeDoux, 1998; Panksepp, 1998). A menu of model-specific protocols looking at the re-evaluation of specific thoughts and/or catastrophic misinterpretations via verbal reattribution and behavioral experiments have performed very well across a range of groups such as

those suffering with social anxiety (Fedoroff & Taylor, 2001), Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (Ehlers et al., 2003, Ehlers, Clark, Hackmann, McManus, & Fennel, 2005) and Panic Disorder with or without agoraphobia (Clark et al., 1994, 1999). Cognitive- Behavioral Therapies (CBT) for anxiety related disorders have been found to perform well but with a recognition of a need for further research and improvement (NICE, 2004). More recently classic CBT models have been supplemented by interventions

that, instead of looking at the content of thoughts, focus on the individual’s relationship with his or her thoughts and feelings. Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (Kabat-Zinn, 1990), Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (Segal, Williams, &Teasdale, 2002), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999), and Meta-Cognitive Therapy (Wells, 1995) have performed well with this client group (see Baer, 2006; Cullen, 2008; Wells, 2008 for reviews).

Research and clinical practice indicates that one area, in which we may need to look at improving anxiety-focused approaches, are for those individuals who are highly self-critical and experience shame. Such psychological phenomena have been found to be highly associated with each other (Andrews, 1998; Gilbert, 1998; Gilbert & Miles, 2000; Tangney & Dearing, 2002) and highly prevalent in those suffering with such difficulties as social anxiety (Cox et al., 2000) and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (Brewin, 2003; Lee, 2005). There is evidence that individuals with high levels of selfcriticism and shame may do less well with standard therapies (Rector, Bagby, Segal, Joffe, & Levitt, 2000). Hence there maybe a need to look at developments to traditional and specifically focused therapies to address this.

A second group of individuals who appear to do less well with standard CBT approaches are those who agree in principle to an alternative way of thinking about things but report not feeling any different. In sessions they may say such things as “I know it is highly unlikely that something will happen to my son but I don’t feel it, I am not reassured by the evidence,” “I know I won’t lose control but it still feels like it,” or “I know I am not bad but I still feel it.” Beck, Rush, Shaw, and Emery (1979, p. 302) suggest “the therapist can tell the patient that a person cannot believe anything ‘emotionally.’ . . . When the patient says he believes or does not believe something emotionally, he is talking about degree of belief.” Gilbert (1989, 1993) argued that beliefs could be driven and textured by core innate systems regulating threat and safeness evaluations, and that cognitive processing and emotional processing interact but should not be conflated. Neurophysiological evidence shows also that mechanisms underpinning emotion and those underpinning cognitions are separate and have complex interactions (Panksepp, 2007). To compound this problem, cognitive therapist sometimes use the concept of information processing and cognition interchangeably as if they are equivalent, which they are not. “Cognition” is not just information processing. One’s computer and DNA are information processors but do not have cognitions (Gilbert, 2009a). Indeed within the cognitive traditions the complexity of the interaction between emotional and cognitive processing has been addressed. For example, Teasdale and Barnard (1993) proposed two levels of meaning, that account for an intellectual and emotional belief, or “knowing in the head” versus “knowing in the heart.” As Teasdale (1997, p. 146) notes, at the propositional level thoughts such as, “I am worthless,” are simply statements of belief—propositions about properties of self as an object. At the implicational level, however, such a statement represents a rich activation of affect and memories associated with experiences of being frightened, rejected, or shamed. Stott (2007) also addresses this important question, of what he calls “the dissociation between emotion and cognition” in important and helpful ways. Behavioralists using classical conditioning models have always argued on the importance of new learning in the context of affect. What Compassion Focused Therapy adds is that this affect sometimes needs to be positive, especially that associated with affiliation and reassuring. Moreover CFT argues that some individuals are fearful of certain types of positive affect especially those linked to compassion, helpfulness, encouragement, and forgiveness. The inability to experience certain types of positive affect leaves the threat system poorly regulated. Gilbert’s (2000, 2005, 2009b) Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT) and Compassionate Mind Training (CMT) has its scientific and theoretical roots in neuroscience models of emotion, and evolutionary psychology models of human motivation—especially research in attachment (Gilbert, 1989, 2009b) and belonging (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). The basic propositions of this model, with details of the three affect

regulation systems that are important to CFT, are outlined by Gilbert (this issue).

The specifics of the therapy were originally developed as an antidote to shame and self-attacking. The theory not only attributes problematic levels of anxiety to an overactive or oversensitive threat system and subsequent appraisals, but, in many cases to underdeveloped regulation of the threat system by other systems, in particular that of endorphin-oxytocin linked soothing system. It proposes that if the soothing system isn’t working particularly well or accessibly then methods such as exposure and cognitive interventions may struggle because the person doesn’t possess the emotional system necessary to experience alternatives, especially those of a verbal nature, as calming, soothing, and reassuring.

In terms of the formulation, the therapist first develops a shared understanding of the origins of a person’s difficulties and distress, as understandable anxiety regulation efforts, utilizing education about how our threat systems work. For individuals experiencing high levels of shame in particular, this is designed to be normalizing, depathologizing, destigmatizing and deshaming. Second, therapists provide a clear rationale and method aimed at “toning up” the affiliative and soothing affect regulation system so that it can then be recruited to help regulate the threat and drive systems.

This latter component is clearly distinct from many other forms of therapy for anxiety in which the emphasis lies in only “toning down” problematic emotions associated with activation of the threat system such as anxiety, anger, fear, and sadness, via verbal and behavioral challenging of thoughts, beliefs, etc.

Background to the CFT Approac h to Anxiety

CFT locates many of our emotional difficulties to the way in which our brains have evolved, and now interact with very different environments from which they originally evolved. Rather than thinking of conditions as pathologies, CFT sees many of them as understandable glitches and difficulties associated with our tricky brain. It notes that all of us just find ourselves here with a brain we didn’t design and life experiences, that have shaped us, that we did not choose. This is the philosophical basis for the therapeutic stance, that not only impacts on the client’s psychological well-being but also the therapist’s. Such a stance differentiates fault, blaming, and shaming (we did not choose our brains or our early experiences that gave rise to our safety behaviors and emotional difficulties) and responsibility (only through our own actions and efforts will change occur), is accepting, validating, and encouraging.

More specifically, terminology that emphazises “common humanity” and a shared evolutionary perspective serves to unite rather than differentiate therapist and client and can have a significant and profound effect on the message conveyed in therapy at many levels. Statements such as “we have a complex brain, it’s not our fault we . . . or it is understandable/makes sense to feel . . . in this situation” are commonly heard and offered repeatedly by the therapist. This is done in a soothing manner throughout the journey together. Helping the individual to connect with this message emotionally is part of the therapeutic work.

In order to engage emotionally the therapist teaches the individual to engage with a “compassionate mind” via the practice of various imagery and behavior exercises. Just as we can activate anxiety so the therapist can also help the individual activate wise compassion—such as engaging in soothing breathing rhythm and imagining oneself to be a compassionate person; imagining oneself at one’s best and as one would really

like to be. That then becomes the position to slowly reflect on the process in the therapy. The therapist is trying to create a brain state which brings online, capacities for empathy and reflection (see Tirch, this issue) before engaging in complex work. Creating these brain states first can facilitate the therapy to work. CTF also focuses on the therapeutic relationship and the microskills of that relationship—such as pacing, voice tone, emotional attunement, playfulness, support, encouragement, boundary setting and so forth.

The Threat System

Anxiety, of course, is about threat processing. The kinds of anxiety disorders that CFT is especially concerned with are those associated with shame, self-criticism, and fear of engagement. Such individuals can struggle with standard CBT. In CFT great emphasis is placed on conveying to the individual the incredibly important role of the threat system.

Understanding the emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and physiological responses of the threat system is key. More specifically it evolved as a self-protection system, is not their enemy, nor something to be got rid of but something to be worked with and brought into balance with other systems.

So the therapist explains that the threat system exists because without it living things (including us) wouldn’t survive. Its role is to detect and warn us about potential threat and enable us to respond quickly. We experience automatic physiological reactions, a rapid activation of emotions (e.g., anxiety, anger), behaviors (e.g., freeze, fight, flight, submit), and cognitive processes (e.g., selective attention, black/white reasoning. jumping to conclusions). These are called “better safe than sorry” processing

The therapist normalizes the tendencies for these reactions. For example, if an animal calmly eating in a field hears a sound behind it, it will become alert and possibly run away. Nine times out of ten there was no need to run and they have lost good feeding time in the process. However, they are safe. The tenth time there may well be a predator. So their overcautious, “better safe than sorry” thinking was incorrect nine

times out of ten but they survived. The animal that decided to go for a more laid-back approach to life and ignore the sound would have been okay nine times out of ten but the tenth time is dead.

Discussing with individuals that their system is designed to catastrophize, and learning to identify “better safe than sorry thinking” helps to normalize their experiences. In addition the therapist points out, for example, that threat emotions are designed to turn off positive emotions—to enable the focus on the threat; this can be helpful for people who struggle with comorbid depression.

For many individuals, the threat system can be extremely sensitive. We can detect this sensitivity using various physiological measures (e.g., fMRI) and can detect changes in (for example) amygdala activity (LeDoux, 1998). This may be attributable to independent or interrelated factors. First, the individual may have grown up and experienced an environment in which physical, social, and or psychological threat was

common. As such the need to detect and react to threat is heightened. Alternatively they may have grown up in an anxious environment whereby significant others modelled and reinforced high levels of threat processing therefore transferring this to the child via learning and genetics. Anxious parents, for example, may try to prevent their children from feeling anxious by encouraging avoidance. This may be partially because an anxious and stressed child is aversive to many parents and they may, for example,believe that preventing their children from experiencing anxiety is a kind thing to do.

So, if the child becomes anxious about going to a party, for example, and the parent says “that’s okay you can stay with me,” the child never learns how to tolerate anxiety nor the social skills of meeting new people in that kind of social situation. Hence the parent models and teaches the child “better safe than sorry” and a range of safety behaviors that have unintended consequences—lack of learning how to tolerate and cope with anxiety, lack of the opportunities to learn that parties can be fun not just threatening; lack of opportunities to develop skills for social relating, making friends, and sharing in such contexts. Clearly, it is important for therapists to distinguish between threat sensitivities that have come from a traumatic or frightening environment (trauma related) verses those that have come from a lack of opportunity to learn how to tolerate and deal with anxiety.

So CFT spends a lot of time in helping people recognize that their brains are set up to be able to generate high levels of anxiety, and at times to make mistakes—which of course is not their fault.

Understanding Safety Strategies

CFT places the development of safety strategies, in a whole range of contexts, as key to understanding the origins of what may be traditionally described as “psychopathology.” For example, children who are fearful of their hostile parents may develop safety strategies linked to monitoring their own behavior, trying to ensure they don’t activate anger in the parents, and self-blame if they do. Thus self-monitoring, submissive

behavior and self-blaming in the context of powerful threatening others can be seen as very understandable safety strategies (Gilbert, 2007, 2009b). Although such thinking and behaving, when carried on into adult life, could be seen as a distortion, in CFT the emphasis is placed on understanding their better-safe-than-sorry function and protective value rather than the degree to which it is a reflection of reality. Of course,

as with all safety behaviors there can be unforeseen and unintended consequences which themselves become the source of further difficulties. As such, individuals who are anxious and self-blame might not learn how to be assertive or sort out conflicts with other people.

Regulation of the Threat System via the Soothing System

With the evolution of mammals, the attachment system has enabled parents and key individuals to act as threat regulators and soothers for their offspring’s arousal and distress (Bowlby, 1969). This means that the brain has evolved special mechanisms to be sensitive to the care and kindness of others and to respond by calming down and reducing threat sensitivity (Gilbert, 2009b). A parent who is regularly able to sooth a

distressed infant is stimulating pathways in the infant’s brain which will be available to be activated by self-soothing in later in life. More specifically the connections between the limbic system (home to fast-track, automatic, and nonconscious threat processing) and the prefrontal cortex are strengthened. A child from a secure and affectionate background will still become sensitive to certain threats, and quick to notice and react, but this will also quickly be followed by recruitment of the prefrontal cortex, as well as other areas of the brain, to appraise and regulate this reaction in light of a broader range of information. Even in the absence of others, an individual who has benefited from good early attachment can self-sooth and self-regulate—and this is linked to resilience. Individuals who have had fewer opportunities for the development of a soothing/safeness affect system may not have learnt and may not be able to regulate or “calm down” the natural propensity for high threat reactions.

So a key message is that human beings have evolved a very complex brain, and it is important to recognize just how tricky it is. This is especially true of the threat system (Gilbert, 2009b). People working with more complex anxiety disorders should be familiar with these complexities; for example, within the threat system emotions canconflict (e.g., people might become anxious at being angry or angry at been anxious), there are different memory systems that code for trauma (e.g., amygdala body-based memory and event memory); anxieties can arise from approach avoidance conflicts (e.g., wanting to leave an abusive marriage but being frightened and uncertain of doing so—or frightened of acknowledging anger toward a particular parent). CFT points out that different brain states (e.g., the state of depression) alter information processing routines making threat processing much more prominent. CFT emphasises the development of safety strategies as ways of self-protection whose function must be clearly understood and delineated in all their complexity—not seen as pathologies.

Reviewing this information helps us be more understanding of what it is to be human, more accepting of the difficult situations people often find ourselves in, and also understand why we often (over)react the way we do. Subsequently, we may experience less self-criticism and shame enabling the individual to begin to focus on management and responsibility as opposed to working on a disorder, maladaption, distortion, or pathology.

First described in 1892 by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, but largely forgotten for the next century, the theory of neuroplasticity describes the ability for all areas of the brain, and not just areas such as the hippocampus and dentate gyrus, to constantly evolve and change. Although it is certainly true that such development is more efficient during early childhood and puberty, there is a growing and clear body of evidence that

the brain can develop at any part in our lives, even in old age. As such the question is where we wish to concentrate our efforts and develop new potentials. Certainly with many individuals we would propose that work on developing the soothing system is highly important. Analogies with physiotherapy are helpful here—the systems model gives the rationale for why we need to concentrate on “toning up” the soothing system while the concept of neuroplasticity allows us to demonstrate that concentrating our efforts on this is worthwhile, brains do change (Begley, 2007).

Compass ion and Anxiety

Compassion means different things to different people, individually and culturally, so it is important that both therapist and client develop a shared understanding of the term. This article cannot go into the different definitions of compassion but a good starting point is the Dalai Lama’s view that states that compassion is associated with a sensitivity to distress in self and others with a motivation to relieve it—so sensitivity and

motivation become key. Gilbert (1989, 2000 2005a, 2009b) acknowledges the debt to Buddhism but argues that compassion evolved out of caring behavior and for its full functioning requires the integration of a number of different components of mind. These are outlined clearly in Gilbert’s article in this issue. An important point to discuss with clients is that compassion is absolutely not about “hearts and flowers,” “treating oneself,” “abdicating responsibility,” and “doing whatever one feels like.” On the contrary, CFT spends a great deal of time exploring the person’s ability to be kind, supportive, and nurturing toward himself or herself, in contrast to being self-critical and subsequently behaving in ways which advance his

or her welfare. It is about generating the strength and courage, for example, to face the world after being indoors for 10 years, standing up for oneself in the face of an unhelpful relationship, or recognizing and validating feelings of anger and sadness through kindness and understanding rather than self-bullying, self-criticism, and hostility.

Blaming verses taking responsibility

CFT makes a clear distinction between shame and guilt. Shame is focused on a negative (inferior, inadequate, bad) self with self-criticism. The emotions are threatening ones of anger, anxiety, or disgust, and behavior is focused on repairing/avoiding (further) damage to the self. In contrast guilt focuses on being open and taking responsibility for one’s behavior, and if one has done some harm to oneself and others, having feelings of sorrow and remorse with efforts at appropriate reparation. In shame the attention is self-focused, in guilt it is other focused. Shame does not require much empathy whereas guilt does (Gilbert, 1998, 2009b).

Case Example: Using the Three Systems Model to formulate and identify the Therap eutic Focus

CFT monitors carefully the emotional tones of people’s efforts in working with their anxiety. This is done in a number of ways such as practicing compassionate voicing, compassionate thinking, using compassionate images, and generating compassionate behavior. To indicate how CFT is integrated into cognitive behavioral approaches this article will now outline some key features of a case. In order to avoid identification the case is a synthesis of a number of individuals.

Stephen came to therapy with very high levels of anxiety. He was clearly frustrated that he had “not achieved anything, despite being pretty bright” and frustrated because despite his best efforts he could not conquer his anxiety. Stephen had had a difficult childhood. His mum had been in and out of hospital due to breast cancer since Stephen was born. She eventually died “out of the blue” when Stephen was 8, leaving his dad and his two younger siblings.

After explaining the basic three circle model, and the power of our thinking and imagery to stimulate different systems of the brain, we formulated Stephen’s circumstances using this model rather than the more regularly used four column CFT formulation diagram. This was because Stephen had found the three circle system extremely empowering and normalizing of both his difficulties and his needs (see Figure 1).

Starting with the soothing/safeness system we discussed and documented that Stephen had limited opportunities to develop this extremely important system due to his mum’s absence from the family home, the impact her illness had on her while she was at home and his father’s functional rather that emotional role in the family.

In contrast to this underdeveloped system, Stephen’s threat system was discussed and formulated as extremely well developed, given the circumstances of his childhood. Of note we found it beneficial to differentiate between historical (H) and current (C) threats (see Figure 1).

Historically his mum’s illness meant there was a lot of focus on illness within the family. This anxiety understandably lead to a more pervasive threat focus about a whole range of things. Stephen’s family moved three times while he was growing up, initially to be closer to the specialist hospital where his mum was being treated. Following his mother’s death they moved to be near other forms of social support and

again when Stephen’s father changed jobs. Stephen reported “struggling” with friendships and with schoolwork and this was met by criticism from others.

Stephen experienced a threatening internal world in which he perceived himself as “different” and not like others. He believed he thought differently from others, had angry thoughts and emotions, and this lead to him withdrawing and being defensive at times, at other times attacking or submissive, but always “on guard” or on the watch for potential threat from others or potential threat from his own internal world. He was also very anxious about this own mental health.

Stephen’s drive system was not about seeking pleasure, but rather avoiding negatives and threats; for example, achieving to avoid rejection. He reported being “on the lookout” and monitoring all the time, both his internal thoughts, fantasies, and emotions and external world pertaining to other people. He strove to be like others or what he perceived he should be, and he tried to achieve at everything. Stephen reported

that he was driven to make himself a better person and achieve his “true potential” and it was his self-critic that he thought would best help him achieve this.

So Stephen reported feeling a huge amount of anxiety and worry. He felt exhausted due to the effort required to achieve his goals and shame associated with how he felt and how he coped with things. Stephen felt dislocated from others and hostile toward himself. Profound sadness, depression, anxiety, and a sense of “nothing inside” were all experienced and conceptualized as unintended consequences of both his situation and his best efforts to deal with life.

The therapist discussed with Stephen how a lot of what was happening for him was perfectly understandable and distressing consequences from the life he had had, the struggles that he had had to cope with (the cancer and then death of his mother), and what that struggle had done to his inner world. For example, his experiences had stimulated both fear and anger—because he both wanted and loved his mother but was also angry he had to have a mother with cancer; then there was disappointment

with his father who was not much of a soothing agent and lost in his own worries and distress. When he encountered anxiety and bullying, when trying to fit into new schools, there was no one to help him and he felt very alone. As Stephen came to understand what had happened to him he gradually became more compassionate and caring for the child who had had to go through all that—he became able to recognize

the natural fears and safety behaviors that he had automatically developed, and how they had given rise to the unintended consequences and current emotional problems.

They were not evidence of a bad person “going mad,” being inadequate, or needing to prove himself.

In CFT a core component is the functional analysis of the protective nature of safety strategies—and developing deep compassion to that part of the self that had to develop them. Of note, CFT is not overly focused on identifying core beliefs or schema—although if they arise and seem useful they could be a focus.

This conceptualization was experienced as hugely validating to Stephen. He was able to look at his present difficulties in the context of early life events. He was also able to acknowledge that some of the things he now did to protect himself also had unintended consequences. In the short term they were deemed appropriate or helpful but in the long term lead to further difficulties. Experiencing the formulation as a compassionate view of Stephen’s story also set out a credible, scientific rationale for why concentrating on developing self-compassion was important to help regulate his very well-developed threat and drive based systems.

Greatest fears associated with the development of compassion

Discussion was spent on exploring the value of developing the soothing circle via compassion and collaborating on this as a therapeutic goal. So, following Stephen developing a rationale for working to “tone up” the soothing system, the first “exercise” Stephen embarked on was discussion around his greatest fears associated with the development of different components of compassion. This highlighted areas that

may have acted as blocks in therapy. For example, it elicited fears that Stephen would start to grieve and feel overwhelming sadness if he started to develop compassion.

As such this concern was normalized as understandable, (isn't this CBT? karen) the process of grief was discussed and he was reassured that wherever the journey took us we would “walk the path together.” In addition, we explored this in terms of “step at a time” with him in

control—that getting in touch with grief need not be “all or nothing.”However painful, emotions like this, and unprocessed affects and memories need to be addressed—and in this sense it is similar to CBT approaches aimed at working with trauma. The ability to tolerate the emotions associated with memories is extremely important. Most trauma work focuses on fear but Gilbert has highlighted the importance of focusing on grief and the fear of the pain of grieving. In the case of grief it’s a process that can take some time. In CFT working with trauma and loss memories can play a key role in recovery (Gilbert & Irons, 2005). (I'm not sure I agree with this concept. Sometimes I panic just because. I think it is stupid that anyone would believe I am panicking because of the way I was potty trained. I'm just saying! karen)

Developing a “soothing breathing rhythm”

A key aspect of CFT is the awareness of body processes and in particular the value of slowing before engaging with difficult material. A useful element which links with, but is different to mindfulness, is soothing rhythm breathing—where the individual learns how to breathe slightly slower and slightly deeper and focus on the experience of “body slowing.”

As a preparation for some of the imagery exercises we spent time building up a

soothing breathing rhythm. As with many of the exercises there are a number of ways one can do this. While some individuals take to it immediately, others find it helpful to try different methods until one is found that is useful. As such it is always beneficial for the stance to be explorative. Each exercise is set up as an opportunity for learning and differentiating what is helpful from what is not. The therapist takes part in such

exercises rather than merely facilitating them. (hate this whole idea. mostly because i feel i am giving control of myself over to another person. I always hated these "find your special place" exercises! All I do now is determine I need to focus, place one hand on my chest and one hand on my stomach. I have to breathe by raising the hand on my stomach. This causes me to breathe slower and deeper in addition to distracting me from the sound of my heartbeat! karen)

Although Stephen initially attempted to concentrate focusing the mind on the nose septum, between the nostrils, Stephen found that simply concentrating on the breath was the most helpful method. He was initially uncomfortable with closing his eyes so we started off simply looking toward the floor then built up the time spent in this exercise. Without prompting he started to close his eyes approximately 3 weeks

into the practice. Instructions given were akin to those used in mindfulness, normalizing digressions of the mind but when one was mindful of them, bringing the attention back to the breath. Stephen practiced this exercise outside of sessions supplemented by a taped recording of the specific part of that week’s session in which we practiced the exercise.

Compassionate Imagery

CFT has developed a wide repertoire of imagery exercises from a range of sources, such as Buddhist meditations and clinical feedback (see Gilbert, 2009b, 2010, and www.compassionatemind.co.uk). As with the previous exercise Stephen practiced a range of exercises, finding the “ideal compassionate self ” (Gilbert, 2000) to be the most productive in giving him a feeling of warmth and compassion. This was then the compassion focus that we concentrated on and used throughout our work together.

These exercises attempt to create a brain state (e.g., stimulating the insula; see Tirch, this issue) which facilitates the processing of threat-based material. Compass ionate Re-evaluation Records (CRRs)

As an adaption to classic CBT thought records, CRRs were used to bring Stephen’s awareness to empathy for his own distress, compassionate attention, compassionate thinking, compassionate acceptance, and compassionate feeling (see Table 1 for a sample CRR worksheet drawn up over one therapy session).

Although Stephen reported getting a lot out of the reframing exercise ( isn't reframing standard CBT? karen), compassionate feelings were enhanced further by then using the compassionate-self imagery prior to rereading the CRR. This helped Stephen call on compassionate feelings and a frame of mind to review his alternative thoughts. The exercise involved him staying with each entry until Stephen reported that he truly felt reassured and accepting of such statements and they had more emotional meaning.

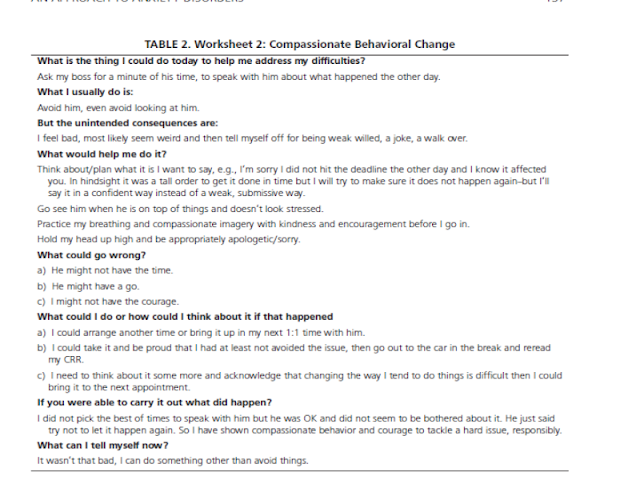

Having proceeded through the previous exercise Stephen reported an increase in his motivation to face that which he often avoided. This was a pattern that was more evident in the early days of therapy, namely, to complete CRRs before addressing his behavior; however, as therapy progressed compassionate behavioral change became more of a primary focus. For example, following a difficult situation at work, Stephen decided to speak to his boss instead of withdrawing and avoiding. To facilitate this he completed a behavioral change worksheet (Worksheet 2).

In future worksheets differentiations were often made between those behaviors aimed at activating the drive system from those aimed at the affiliative. As such an emphasis was placed on achieving “balance” that counteracted the often experienced, but less beneficial pull toward centering much of therapy around the positive affect system of achievement drive.

Compassionate Letter Writing

Throughout therapy Stephen was asked to engage in compassionate letter writing and bring his work to sessions. These letters can be various. There is good evidence that reflective writing about oneself and one’s experiences (Pennebaker, 1997) and compassion- focused letter writing (Leary et al., 2007) can be very helpful in assimilating painful life events and facilitate coping with painful life events. Stephen’s letters were about himself and to his mother. This allowed him to learn how to articulate feelings and to be accepting and tolerant of them. Letter writing enabled him to work through and process memories. (It is called blogging! karen) Sometimes Stephen would read the letter to the therapist and at other times the therapist would read the letter to Stephen in as compassionate and understanding a way as possible. These “letter sharing” sessions were moving and gave an opportunity for reflection and generating new points for view outside of session.

This helped him practice self-compassion and acceptance and also allowed the detection of signs of self-criticism or hostility. Guidelines for writing such letters can be found on the Compassionate Mind website (www.compassionatemind.co.uk).

Self-Criticism

Self-criticism is found to be a major problem for many people meeting criteria for “anxiety disorders.” This can be a addressed by putting oneself into “compassionateself” stance and then viewing one’s self-criticism with compassion until one begins to change—which for some people can take time. By addressing self-criticism “compassionately” people begin to recognize when it arises and gradually see it as a cue to refocus on compassionate thinking. The idea is not to directly challenge or fight with the self-critical self, because that just keeps the threat system going, but to: “notice selfcriticism, take a breath and refocus,” “notice, take a breath and refocus,” “notice take a breath and refocus.” (The issue is slightly different if the critical voices are identifiedas a past abuser—see Gilbert, 2010). Individuals, including Stephen, typically become surprised at just how much they are self-criticizing on a day-to-day basis, but this also gives them the opportunity a practice self-compassion regularly.

Conclusion

This article has outlined some of the basic ideas that illustrate a compassion focused therapy approach to anxiety. An important principle here is recognition that sometimes simply trying to change processing within the threat system is insufficient. The reason for this is because one of the major regulators of threat processing comes from the “soothing system” and if that’s not working properly individuals can have intellectual understanding but not emotional connection. Helping bridge that gap has

resulted in the development of CFT.

Compassion textures the whole therapy including the therapeutic relationship and the formulation. When individuals develop an appropriate formulation they’re much more likely to be compassionate to the problems rather than ashamed of them. Such formulations are part and parcel of the development of wisdom—which is used when developing the compassionate self. In other words, wisdom arises because one has better insight into the origins and functions of one’s safety behaviors, recognizes

the evolutionary elements (that we all just find ourselves here; we did not choose our brains), and shift toward taking compassionate responsibility. This enables people to begin to do the emotional work necessary and engage with frightening material or actions (e.g., exposure).

CFT builds on and utilizes other therapies, because this is the practice of science—we should not keep reinventing the wheel. CFT always involves collaborating with the individual, sharing insights from science and exploring how to use these models to bring better balance to our minds. As such the hope is to learn from science, and each other, in order to promote well-being. a client’s own conclusion to cft

The following words are a personal reflection from an individual who engaged with CFT for anxiety over an eight-month period with the author. Although she wished to contribute to the paper, for personal reasons she asked to remain anonymous.

I used to be really down on myself and got depressed because I got so anxious about things. I couldn’t cope, I used to shake all the time and avoid things. I used to think there was something wrong with me, somehow I was different, defunked, incapable. My family would get really frustrated with me and used to say I had to sort it out, pull myself together and get on with things. My (previous) therapist told me I had to work on my thinking ‘cos it was dysfunctional and “twisted”. Sometimes talking to people helped, they reassured me thatthings were going to be ok …… if only I worked at it harder. The thought diaries helped when we did them initially but the effect did not last. I felt as if I was useless with them. I used to

think if only I could “get it” things would be better but I never “got it” properly. I felt alone, different, and peculiar.

Now (in CFT) I know I had reason to be anxious and fear things. Now I know what I did to protect myself had unintended consequences. Now I have the courage to face things, I can say “so what if I get anxious. . . . That’s me. . . . You would too if you had experienced what I experienced.” I know I will have to continue to work on things, there is no quick fix, it’s going to be a life-long thing because I can’t just get rid of certain parts of my brain, I have to strengthen new parts day by day, week by week. But things will continue to get better.

The exercises help me “feel” different. Sometimes they put me in a better frame of mind so I can take on board positive things people have said, things I have written down, rather than discount them. Other times they just help me put things in perspective. . . . Feel warm regardless of everything . . . so what if somebody said that to me. I don’t need to go into it, I am an ok person.

It helps to know that Mary [compassion focused therapist] has to practice and so do I. There’s no shame in that. . . . In fact it is actually exciting to think that the journey isn’t over. . . I will continue to grow and blossom.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV). Washington, DC: APA.

Andrews, B. (1998). Shame and childhood abuse. In P. Gilbert & B. Andrews (Eds.). Shame: Interpersonal behavior, psychopathology and culture (pp. 176-190). New York: Oxford University

Press.

Baer, R.A. (2006). Mindfulness-based treatment approaches: A clinician’s guide to evidence base

and applications. New York: Academic. Baumeister, R.F., & Leary, M.R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497-529.

Beck, A.T., Emery, G. & Greenberg, R.L. (1985). Anxiety disorders and phobias: A cognitive perspective. New York: Basic Books.

Beck, A.T., Rush, A.J., Shaw, B.F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New

York: Guilford.

Begley, S. (2007). Train your mind, change your brain. New York: Ballantine Books.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment. Attachment & loss, vol. 1. London: Hogarth Press.

Brewin, C.R. (2003). Post-traumatic stress disorder: Malady or myth? New Haven, CT: Yale University

Press.

Carter, C.S. (1998). Neuroendocrine perspectives on social attachment and love. Psychoneuroendrinology,23, 779-818.

Clark, D. M., Salkovskis, P.M., Hackmann, A., Middleton,H., Anastasiades, P., & Gelder, M.

(1994). A comparison of cognitive therapy, applied relaxation and imipramine in treatment

of panic disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry, 164, 759-769.

Clark, D.M., Salkovskis, P.M., Hackman, A., Wells, A., Ludgate, J., & Gelder, M. (1999). Breif

cognitive therapy for panic disorder: A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Consulting

and Clinincal Psychology, 67, 583-589.

Cox, B.J., Rector, N.A., Bagby, R.M., Swinson, R.P., Levitt, A.J. & Joffe, R.T. (2000). Is

self-criticism unique for depression? A comparisonwith social phobia. Journal of Affective

Disorders, 57, 223-228.

Cullen, C. (2008). Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT): A third wave behaviour

therapy. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy,36, 667-673.

Depue, R.A. & Morrone-Strupinsky, J.V. (2005). A neurobehavioral model of affiliative bonding.

Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28, 313-395.

Ehlers, A., Clark, D.M., Hackmann, A., McManus,

F., & Fennel, M. (2005). Cognitive therapy for PTSD: Development and evaluation. Behaviour

Research and Therapy, 43, 413-431.

Ehlers, A., Clarke, D.M., Hackmann, A., McManus, F., Fennell, M., Herbert, C. et al. (2003).

A randomised controlled trial of cognitive therapy, self-help booklet, and repeated early assessment as early interventions for PTSD. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 1024-1032.

Fedoroff, I.C., & Taylor, S. (2001). Psychological and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 21, 311-324.

Gilbert, P. (1989). Human nature and suffering. Hove and London (UK): Erlbaum.

Gilbert, P. (1993). Defence and safety: Their function in social behaviour and psychopathology.

British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 32, 131-153.

Gilbert, P. (1998). What is shame? Some core issues and controversies. In P. Gilbert & B. Andrews

(Eds.), Shame: Interpersonal behaviour, psychopathology and culture (pp. 3-36). New York: Oxford University Press.

Gilbert, P. (2000). Social mentalities: Internal “social” conflicts and the role of inner warmth and compassion in cognitive therapy. In P. Gilbert & K.G. Bailey (Eds.), Genes on the couch: Explorations in evolutionary psychotherapy (pp. 118-150). Hove: Brenner-Routledge.

Gilbert, P. (2005). Compassion and cruelty: A biopsychosocial approach. In P. Gilbert (Ed.),

Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy (pp. 9-74). Hove, UK: Routledge.

Gilbert, P. (2007). Evolved minds and compassion. In P. Gilbert & R.L. Leahy (Eds.), The therapeutic

relationship in the cognitive behavioural psychotherapies (pp. 106-142). Hove, UK: Routledge.

Gilbert, P. (2009a). Moving beyond cognitive therapy. The Psychologist, 22, 400-403.

Gilbert, P. (2009b). The compassionate mind: A new approach to life’s challenges. New York: New Harbinger.

Gilbert, P. (2010). Compassion focused therapy: The distinctive features. London: Routledge.

Gilbert, P., & Irons, C. (2005). Focused therapies and compassionate mind training for shame and self-attacking. In P. Gilbert (Ed.), Compassion: Conceptualisations, research, and use in psychotherapy (pp. 263-325). London: Routledge.

Gilbert, P., & Miles J.N.V. (2000). Sensitivity to put-down: Its relationship to perceptions of shame, social anxiety, depression, anger and self-other blame. Personality and Individual Differences, 29, 757-774.

Hayes, S.C., Strosahl, K.D., & Wilson, K.G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford.

Hofmann, S.G. & Smits, J.A.J. (2008). Cognitive- behavioral therapy for adult anxiety

disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69, 621-632.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living. New York: Delacorte.

Kessler, R.C., Chiu, W.T., Demler, O., & Walters, E. (2005). Prevalence, severity and comorbidity

of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 617-627.

Leary, M.R., Tate, E.B., Adams, C.E., Allen, A.B., & Hancock, J. (2007). Self-Compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: The implications of treating oneself kindly.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 887-904.

LeDoux, J. (1998). The emotional brain. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Lee, D.A. (2005). The perfect nurturer: A model to develop a compassionate mind within the context of cognitive therapy. Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy (pp. 326-351). Hove, UK: Routledge.

NICE. (2004). Guide for anxiety disorders: http:// www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/cg022fullguideline.pdf.

Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective neuroscience. New York: Oxford University Press.

Panksepp, J. (2007). The neuroevolutionary and neuroaffective psychobiology of the prosocial

brain. In R.I.M. Dunbar & L. Barrett (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of evolutionary

psychology (pp. 145-162). New York: OxfordUniversity Press.

Pennebaker, J.W. (1997). Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychological

Science, 8, 162-166. Rector, N.A., Bagby, R.M., Segal, Z.V., Joffe, R.T. & Levitt, A. (2000). Self-criticism and dependency in depressed patients treated with cognitive therapy or pharmacotherapy. CognitiveTherapy & Research, 24, 571-584.

Schore, A.N. (1994). Affect regulation and the origin of the self: The neurobiology of emotional development.Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Schore, A.N. (2001). The effects of early relational trauma on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal, 22, 201-269.

Segal, Z.V., Williams, J.M.G., & Teasdale, J.D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York: Guilford.

Stott, R. (2007). When the head and heart do not agree: A theoretical and clinical analysis of rational-emotional dissociation (RED) in cognitive therapy. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 21, 37-50.

Tangney, J.P., & Dearing, R.L. (2002). Shame and guilt. New York: Guilford.

Teasdale, J. D. (1997). The transformation of meaning: The interacting cognitive subsystems approach. In M. Power & C.R. Brewin (Eds.), The transformation of meaning in psychological therapies: Integrating theory and practice (pp. 141-156). Chichester: Wiley.

Teasdale, J.D. & Barnard, P.J. (1993). Affect, cognition and change: Remodelling depressive thought. Hove: Erlbaum.

Thwaites, R., & Freeston, M.H. (2005). Safetyseeking behaviours: Fact or fiction: How

can we clinically differentiate between safety behaviours and additive coping strategies

across anxiety disorders. Behavioural andCognitive Psychotherapy, 33, 177-188.

Wells, A. (1995). Meta-cognition and worry: A cognitive model of generalised anxiety disorder. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23, 301-320.

Wells, A. (2008). Metacognitive therapy: Cognition applied to regulating cognition. Behavioural

and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 36, 651-658.

No comments:

Post a Comment